|

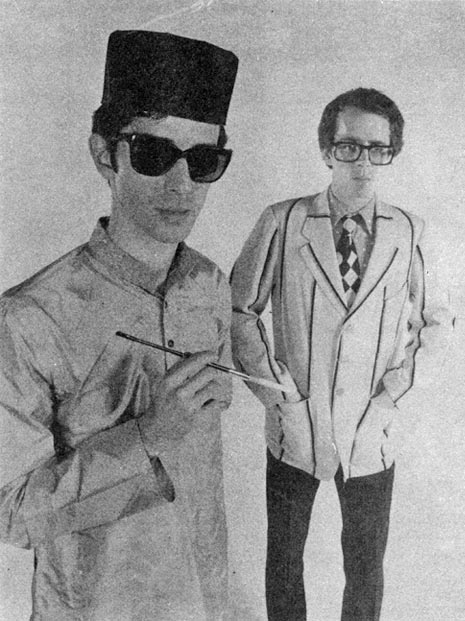

THE MONOCHROME SET Second Interview, 3 December 1980 This is the full transcript of the interview I did for my ZigZag article (issue No. 109, January 1981), after the release of Love Zombies. It took place at the band's management office in Chalk Farm, followed by a photo session at a nearby studio (as far as I can remember). This time all five members of the band, including Tony Potts, were present. Again, I have no prints from the photo session, so I scanned the two images from the magazine article - apologies for the bad quality! |

||

|

B = Bid Q: Why did you release the second album so soon after the first one? B: Technically speaking it was an acrobat move, we were trying to push ourselves to see how much dirge we could produce in such a short time. Financially speaking it was because we needed the money. Q: Did you write the songs just for the album? B: Partly. We didn't necessarily think of playing them live when we were actually writing, we were just trying to get enough songs to put on the album, so we could put it out and get more money for doing it. A couple of the songs we can't do live because they didn't actually come out of having been played live, they came out of rehearsal sessions and straight into the studio. So when you hear them live it might be different. Probably. Q: Are you going to keep releasing records at such a fast pace in future too? B: No. AW: We've learnt by our mistake. B: Yeah, Karma Suture, if people knew how quickly we had to write it... it's quite an achievement. But we don't really want to repeat the experience, because after having written something, it's always better to play it at least at rehearsals, if not live, for a long time before you record it. Because you can iron out the problems in the song, rearrange it ready for recording. After another six months of playing new songs on this album, we'll get a bit annoyed that we didn't have enough time to record it, because we could have recorded them better. We didn't have time to think about it when we were doing the album. So we'll be taking more time to do the other albums. Q: Was anything totally different in the process of making this album from the first one? B: Well, we didn't have a producer on the album, we co-produced with our engineer. In that we had more control over the sound, what was going on in the studio. The studio was bigger, the same studio but it was expanded, sort of bigger apparatus inside the mixing desk and the process. We spent a bit longer time in the studio. Yeah, we just had more control over what was happening. It's pretty well the same process. Q: Who played the piano? B: Depending on what song, either Tom or Alvin. Mainly Tom, I think. Q: It's got really bad reviews in the music papers, well, both the album and the single. How do you feel about that? B: Yeah, the English press... I don't know, it's possibly something to do with the fact that they don't actually like it, in which case I'm not really bothered. I mean, if they don't like us, that's the way it goes. I'm just passing it over, another disaster. Q: Aren't you interested in commercial success? B: Yeah, but there's no use crying over spilt milk, so we don't really bother about it. JD: Having interests in commercial success isn't quite the same as generating it. B: You can't really say anything. I mean, yes, the reviews are bad, yes, we are interested in commercial success and sex as well... JD: Those reviews actually killed my interest in commercial success. B: ... and yes, we know that we aren't commercially successful in this country, and things like that. That's it. We're trying to immerse ourselves in other things. Q: Do you think your fans liked it better than the first one? Because I did. B: Yeah, actually... AW: Some of them do, and some of them don't. B: These Monochrome Set fans who just like the third Rough Trade single and nothing else, or first Rough Trade single and nothing else, I should imagine they probably did, generally speaking, like it at least as well as the first album. It's not spectacularly better than the first album, it's just a bit better. Q: I think the second album sounds more like the Monochrome Set. B: It is because we had more control over it, more control over the sound, whereas the first went through a filter of Bob Seargent doing his thing on it. We were sitting around and he was doing things behind our backs in the studio, little things, which made the first album good, we liked it at the time, but we wouldn't want to repeat. We liked it, that's why we had it and that's why we asked him to produce the second album, but when he said, "I haven't got time for you, boys"... JD: There was more money elsewhere. B: Plus we said we were only asking you... TP: ... because you were cheap B: .... you were cheap. Q: Are you starting to feel sleepy again? TP: What? B: We're starting to go funny, we're dull so to speak, as one tends to, when one is on tour or in between tours. Q: I think the songs on the second album are more like songs - you are actually singing. I didn't like your vocals on the first one, they sounded like... B: My vocals came across better on the second album. I think the first album could have been potentially better vocally, as far as I'm concerned. I sang badly, or the vocals were pushed back into the songs more. The second album is more powerful vocally. I don't think it's necessarily more melodic because of the great production we did, but you notice the vocals more on the second album. For example, on the first album on The Lighter Side of Dating, you hardly notice I'm singing a melody at all. Maybe my fault or maybe the fault of the desk. It's the production, mainly. They're all songs, really. TP: Some people don't think Bid sings at all, some people don't know what singing is. Shouting has come to be called singing. B: That's it, actually. TP: So has music. B: Still, we try to keep happy. TP: People have lived with volume throughout the 70's, and they've forgotten what music really is. When they hear it, they don't think it's music. Q: That's the trouble with the music press, isn't it? The reason why you get bad reviews. TP: I'm glad you said that. B: Well, take for example the type of music Mike likes listening to, which is, generally speaking, a bit unmusical, isn't it? A lot of the things you like? MC: I'm not really interested in music at the moment, I like the people. That's the starting off point, the attitude. B: I don't really know what. I always thought it could never get so bad in this business that people would want to listen to an unmelodic dirge in preference to a melodic one. It surprises me that [first] there was an upsurge of melodic sounds, psychedelic music, then you had heavy metal, then straight into punk. I always thought music is a reaction against one sort into another. Going from punk into unmelodic synthesizer music is a strange reaction. That's my personal opinion, I'm sure Australian Aboriginals don't. TP: That's part of their culture. AW: Maybe one or two do. TP: Your Abo's love a tune. B: I don't care. There are some types of music you can react to physically, and other types mentally. Listening to music you can only react to mentally all the time irritates me after a while. Most well-balanced people like a cross section in their record collection. But people like Mike, listening to DAF all the time is just like one person listening to Beethoven all the time, I suppose, it's a bit dull. The music press is tasteless musically, although they don't actually like talking about the music as such. They're either intelligent people who aren't suited to their job, or intelligent people who have no taste. AW: Or they're not joking. B: Basially, if they like us, they're intelligent people with taste. If they don't, I can't stand them.

Q: What sort of music do you listen to? B: I don't listen to a lot of music. There's bound to be something we all like if you mentioned. Mention a name, go on. I'm sure I could probably find one Bob Dylan song I could listen to without cringing, I'm sure I could find one Sham 69 song... In fact there was one Sham 69 song that they did that was really good. AW: Like the Rolling Stones one. B: When they all dressed up in their headbangers' gear, great. AW: It was just a reject from the standards. B: You could never imagine a Sham 69 fan saying they could listen to the Monochrome Set. Q: What about Joy Division? Do you ever listen to them? B: Funny you should say that. I couldn't actually tell the difference between one song and another. I only heard one of their songs, I don't know what it was called. AW: The one that really sounds like the Doors. JD: All their songs are bad. TP: I tried listening to the album. B: Did Love Will Tear Us Apart get in the charts? AW: Only beause he was dead. B: It was neither here not there, was it? AW: It had quite a good hook, didn't it? LS: I'm quite surprised that it did have a hook. TP: The album I couldn't penetrate at all. If I was to listen to that type of music, I'd listen to someone who did it before. AW: I don't listen to Nazis on principle. LS: Are they really? AW: Well, I just assume that from people who are called Joy Division and changed their name to New Order. Q: What about things like Throbbing Gristle? TP: That's a lot better. In its essential mould it's good, in its category. LS: Throbbing Gristle are actually artists who use sound to sculpt rather than musicians. Q: So you have nothing against "industrial" bands? B: Well, if I could voice my personal opinion about Throbbing Gristle, they are musicians because they have instruments and they play them and make music. If I heard a Throbbing Gristle song on the radio I would turn it off, because I don't like them. LS: Granted the radio isn't their medium. B: If you can't discern what the purpose is by listening to the music, then the purpose is lost anyway. LS: It's not supposed to be music. It's a different field entirely and shouldn't be criticised within the context of music. It should be within the context of Studio International, where it's quite valid. And certainly I would turn it off if I was driving along. Q: What is your purpose in music? LS: My purpose in doing music is... AW: Was. LS: What? I like tunes, and when I started making music, there wasn't enough tunes around. I like putting things together that even I, as the writer, will go around humming after work. TP: That's what happens: we go around humming them and no one else does! B: I think I'm going to come out with a profound observation. TP: I doubt it, but go on. B: I think, if you were, like a writer in the music press, for example - I took the profession out of the air - and being an ordinary person, you would instinctively find melodic, tuneful song to be likeable. Then, after a while, what you'd find intellectually interesting, maybe, would be unmelodic songs, and after a while, perhaps you would get brainwashed by listening to so much unmelodic, untuneful, dirgy crap. Instinctively then, you would find that interesting, you haven't got to the stage yet where you would find the tuneful song interesting [again]. AW: I think that's what we were cashing in on, in fact. B: But if you hang around for 4-5 months, we'll start getting good single reviews. AW: By that time we might be doing something different. B: Maybe they'll re-review something. Maybe they should keep re-reviewing Strange Boutique every year. AW: That would be nice. B: Sort of strange. I'm sure one of those days, one of those writers is going to go down an old country lane, hear an old yokel's song and find it incredibly challenging, the rhythms and all that. 'I'm on my plough - ' TP: 'I'm going to howl - ' B: 'I have a cow - ' Incredibly avant garde. It's so enclosed to be in that situation, where your head is full of music all the time. To be a writer you've got to be interested in music more than an actual musician. Q: Have you sorted out the visual side for the London gigs? TP: I've sorted it out and am going to leave the rest till the night. Yes, we have an idea, we're using lights for a change, reducing the size of the film image use. There's not much you can do within the confines of a rock venue, remember you're only moving into it on the day of the gig. It's restricting. JD: They've been good on occasions, sometimes very good. Q: Someone - actually, Damon Edge of Chrome, the American band, said that films being used on stage is becoming standard avant garde, that everyone seems to be using films... TP: It's OK. It's not a unique idea. We weren't the first to use films and we won't be the last. We might well stop using it because other people are using it. We might try to use the films in another way. We've been through our period of experimenting using films, and we'll come to a conclusion. B: Before someone comes with a lot of money and blows us off stage. TP: I've always rather liked the fact that it's a stage show and not ultra technical. Q: Tuxedo Moon use film images very much like the Monochrome Set's. B: We've done our bit of pioneering for everyone else, taking the stick and letting them reap the virtues. We'll probably go on and pioneer something else now, break a new field, get all the stick, and in 6 months' time someone will reap all the virtues. TP: While we were the only band in our strata of doing what we were doing, and it was always the Human League doing the slides, people would come up and say "hey man, looks like the Human League". Q: When the Monochrome Set song was played on the Japanese radio, the DJ said "they use films on stage, just like the Human League use slides." TP: That's OK, that's a fair comparison. I suppose there's a vague comparison there. It shows how closetted those people are though, they think my sole experience of things visual was the Human League and nothing else. B: None of those people who compared us with the Human League had any foresight at all. TP: There are people like DEVO using films, showing themselves performing songs, which is a different kettle of fish, not the same way as we are at all. Their stage show, when I saw them, was really good throughout the set, but it can't be compared with us at all. They don't use films during the set, or to go with the music they're playing. They're doing a completely different thing, and they're a band who have always done that. For a brief period we were the only people doing what we do.

Q: Films are basically just entertainment in the Monochrome Set shows. Is that right? TP: Like the music. Q: But when you show your films on their own, are they there to entertain? TP: I don't think it would be particularly entertaining, no. B: The object would be the same. TP: The films are given their lease of life by the very fact that they are being played simultaneously with the music. They're silent for a start, so there's not much point other than showing them with the music. They were never made to be seen on their own. I make films to be seen in their own right, which is something completely different, which is like DEVO films, which they show as an extra. The Monochrome Set stage films are never made but for the specific purpose of being shown at a gig. Q: How did you come to use your films for that purpose, for live shows? Did the idea come from you or the band? TP: I got to know the band I happened to be a filmmaker, so instead of joining them and play keyboards, I joined to make films. LS: If he had been a dancer, he would have done a pirouette. TP: Instead of expanding the sound, we expanded the visuals. Q: So it wasn't because it was an interesting experiment from the filmmaker's point of view? TP: Well, it encompasses all those things, you can't help but do that. It can be experimentation, working with musicians and working in different situations, all those things come about when you show films simultaneously with music, so there's a whole range of different things happening within the idea. You don't pop along and say "hey, I feel a bit like being experimental, let's make films to show with the band!" It was much more natural, I make films and that was going to be my contribution if I was going to be part of the band. JD: It was symbiosis. B: When one is being experimental, one rarely knows about it. They call, musically speaking, some of our stuff experimental, but we just bunged it together and it came out like that, like I'm sure Albert Einstein didn't realise he was being experimental when he discovered all his things. He just did them, he was just a natural genius. You just do things because you're interested in them. Maybe that's being experimental. We just did it because it interested us to do it at the time. It did so happen that our lighting show at the time was very dark blue lights, so it was very conductive to having films on, with Tony showing films over us, beside us, whatever. Everything just fitted together. But it didn't occur to us that it was experimental. Usually, when you say things are experimental, you mean it's detrimental to what you were doing before, whereas experimental should mean you're giving up what you were before and trying something else. Q: Would you say the B-side of the single Apocalypso was experimental? B: Er... AW: I'd say it was more of a joke. B: It was a last minute muck around, really. It was... LS: The last day of the term. B: It was getting a telegram saying "do a B side which is different from the album", and looking at our little music sheets and finding we didn't have anything close to put on the B side after already putting everything on the album, we decided to do a dub version of Apocalypso. JD: I'm assured by three of my friends who attend soul discos that, had we altered the vocals, esp. my contribution, it could have been a smash hit 12" disco single. B: Really? It just seemed like an idea at the time. As Andy says, just a joke made by somebody at the time. AW: Seemed like a silly idea, so we did it. MC: I think it's really good. JD: I'm sure we should have sold it on Trojan. Q: Did Andy joining have any effects on your song writing? B: It's the second album... yes, he did write some songs. Q: In what way [did it change]? B: He's just another writer, on the credit side you can see he's written quite a few songs on the album. That's about it, really. On the arranging side he did more. Just a stroke of luck, really. To write songs in such a short period of time. AW: It sounds quite different. B: What, the songs do? AW: I think generally. If I hadn't been in the group, the second album would have been a lot different. B: I don't know, actually. Hadn't crossed my mind. It's a bit wider now, our ability to encompass several different fields of music. It's grown a bit, we can change our moods with more ease, like a well oiled machine. So when a stupid comment like "let's play a Red Indian song" become serious concepts, you know. Q: Do you think your music is physical, dance music, or is it more of a "mental" music? B: I don't think it occurs to us at the time, I mean we don't deliberately do dance music or deliberately do the music undanceable. TP: These questions don't arise. AW: I would prefer it if people could dance to it. But we don't write a song so that people can dance to it. TP: I can dance to Stravinsky's "Rite of Spring" but that's not what you meant. B: When we go on stage and play, I should imagine every number we play, including "Goodbye Joe", people dance to. Q: They dance to that? B: Yeah, when I strum the chords, it's in a certain rhythm and people actually dance to it as well. So I think they dance to pretty well every number we do. AW: They dance like on They Shoot Horses, Don't They? Q: But at the point of writing songs, what sort of music are you actually trying to make? AW: We're not trying to make any sort of music. TP: Yeah. B: You sit down, write something interesting and hope no one's written it before. That's all. TP: You can tell if people have sat down and decided to make anything. There are two different types of creative people: people who sit down and say "I'm going to write a 2-Tone record", and then there are people who want to paint or write a song or make a film and go away and do that perfectly naturally, and that's what it is. You don't have to sit down and say "today I'm going to produce something to dance to, or something that someone can say is punk or 2 tone." You do exactly what you want to do to the best of your ability, and then it might fall into one of those categories, or it may not. It's not a question of trying to produce dance music or trying to produce a film like Godard or like Andy Warhol. AW: That's what a lot of people dislike about us, the fact that one song might be very poppy and another song might be very dirgy. B: I suppose so because, off hand, you get a Genesis fan who'll go and buy a Genesis record whether he likes it or not, because he feels safe with that band. AW: He knows if it's not nice or not. B: He can sit down, wear the same clothes and feel safe with it. Generally speaking, the sound is the same. But people who listen to our music, if they want something more than music or just the silly little vocals that go through feel very unsatisfied. They can't sit down with their Monochrome Set gear, because they don't actually know what it is, they can't stomp along or smoke joints along or whatever they do to certain types of song. AW: ... or wear old socks because they haven't joints... TP: ... or wear pork pie hats... AW: If you come back tomorrow, John might be wearing old socks, that's the thing about this band. B: It's the same with Max Bygraves listeners. We're nothing to do with any youth movement or old age movement. Nothing to do with any movement at all. TP: By design anyway. It might be that other people want to categorise you. By design you don't all sit down and decide "God, what are we going to do, we've got to write a disco hit." B: You get a feeling in the early stages of a song, in the beginning when you're first writing, you can usually tell how it's sounding. AW: Until the rest of the group come. B: Until the rest of the group come, and it changes or it might not. depending on how much you've got down. Like when I wrote B-I-D spells Bid, it was already a jaggy sort of song with a certain time signature, and the the band can't really do a lot more than play what it already was, whereas certain other songs like, God, I don't know what... R.S.V.P., which I don't really want to go into, it's changed a lot from when it first started. Q: R.S.V.P. was an instrumental number at first, wasn't it? B: No. Q: It was... B: No, that's just the intro to the set. Q: Have you got anything besides music that you're engaged in? Any other activities? TP: Eating... B: Are you hungry now? TP: No. AW: Lester's a part time school teacher. JD: I'm a poet. AW: I'm a housewife. What do you do, Bid? Q: You're a housekeeper?? AW: Housewife. I do the shopping, cooking and tidy up around the house. JD: Part-time hypochondriac. TP: Full-time. AW: Will you sell your body for medical research? TP: I do a spot of carpentry and joinery. B: Tony's a carpenter. TP: I've got the marks to prove it. JD: A bit subtle that, for the tape recorder. Q: I think that's it. Anything else you want to talk about? AW: No. (c) Akiko Hada 1980/2019 | ||